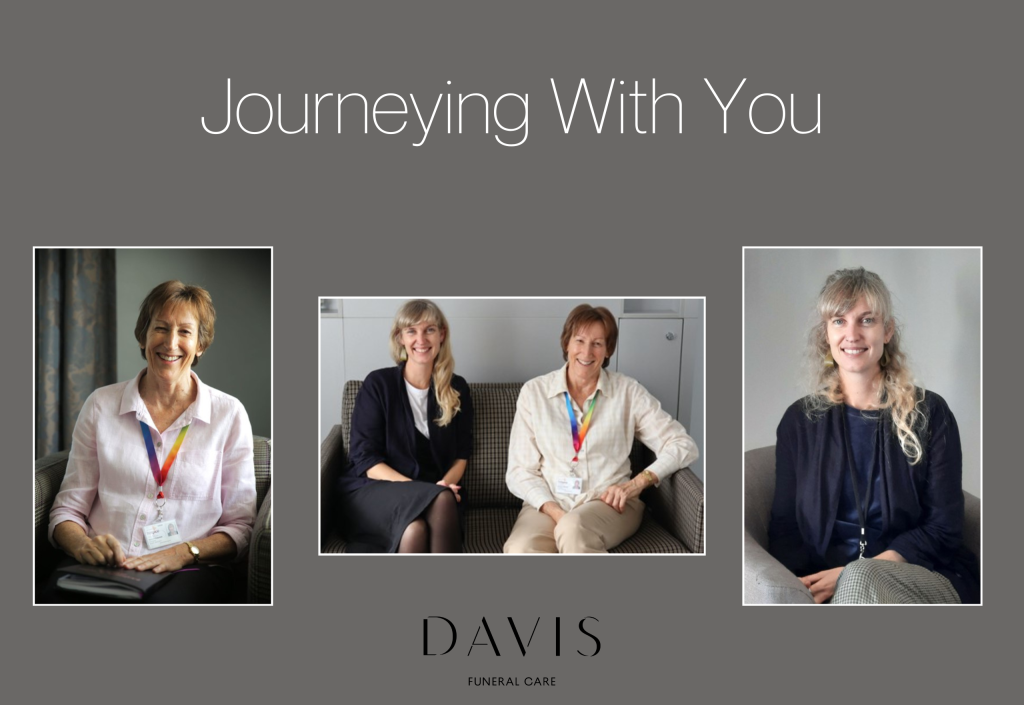

As Palliative Care Counsellors at Hospice West Auckland, Maxine and Amy walk alongside

patients on their end-of-life journey. Sessions can be individual, and/or with couples and

family units. They also work with whānau to help navigate the grief and bereavement

process following the loss of a loved one.

Palliative care counselling is a special role that begins with understanding the unique needs

of each person and what brings them to counselling. “With a patient, we are journeying with

them into the unknown – we go where they go. Sometimes that’s into some really deep,

unknown places that only get revealed when they start having a dedicated space to connect

with what is going on for them,” says Maxine. “Quite often they will have a goal, something

they want to get out of counselling. It’s always patient-led. We are both relational

counsellors, so the person is always at the centre of the counselling.”

Amy explains that although it may seem obvious what brings a Hospice patient to

counselling, it’s important to see what ‘sits on top’ for people: “A person may want to talk

about loss of identity, the frustration they are experiencing, a relationship, or the fear of being

a burden to others,” she explains. “And of course that can change over time, and we’re

alongside adjusting to the change,” adds Maxine. “What might have been a focus at one

point could be something completely different the next time you meet, because life has

changed. It really is going with what is presented each time you come together.”

Maxine was always interested in specialising in grief counselling, inspired by her own

experiences with grief. “Through my training I’ve done other forms of counselling, but I

always wanted to work in hospice – that was my focus,” she says. Amy was also drawn to

working in grief counselling, and did a placement at Hospice West Auckland during her

studies. “I knew then that I wanted to work at Hospice,” she explains. “When working with

people facing end of life, there’s a lot of ‘meaning making’ – the legacy you’re leaving behind

and how you want to be remembered, relationships you have with others, values you’ve

instilled in your children, for example. I think for me it’s always been about being with people

to make sense of their lives, their stories, their experiences.”

At Hospice West Auckland, Maxine and Amy form part of the Social Care team. This

experienced group of individuals provide a wide range of services to Hospice patients and

their whānau, including massage and lymphoedema therapy, music and arts therapy, social

work assistance, spiritual care and acupuncture. “It’s a great team and there is so much

support,” says Amy. “We’re really there for one another – and we have fun too.” The team

work collaboratively with Hospice’s doctors and nurses to identify which patients and families

may benefit from the different social care services. Maxine and Amy also reach out following

a bereavement to see if there is a need for counselling. “We make sure that every patient

who comes into Hospice care is contacted by one of us in the Social Care team to offer that

holistic care,” says Maxine. “We know that our emotional self is just as important as our

physical self, as our spiritual self… we can provide that wrap-around care. And we keep the

relationship open to offer support at any stage of their journey.”

Maxine and Amy run the Bereavement Support Group, a six-week programme for people

who have lost a loved one in Hospice care. The Counsellors gently facilitate each session,

working within the group dynamic and holding a safe space to explore the experiences and

feelings being shared. Each participant is invited to introduce to the group the person they

have lost, which may be a photo, keepsake or any object that represents who they were in

life. It’s a special opportunity to bring their loved ones into the room and talk about who they

were in life, rather than their illness. It is a powerful way to acknowledge that a relationship

doesn’t end when someone passes – they continue with you as part of your life story.

“Groups are really powerful as a way to normalise people’s experiences, and to help them to

feel not so alone. It provides a sense of community and belonging, allowing the opportunity

to connect with others who have had similar experiences,” explains Amy. “Grief can also be

very isolating,” adds Maxine, “and sometimes people need to rebuild their lives after a loss

so it’s really valuable for them to make these connections with others who may be feeling the

same way.” At the conclusion of each six-week programme, the participants have always

continued to meet under their own initiative, maintaining that valuable connection.

The Kowhai Social Group is another weekly programme Amy runs at Hospice House.

Designed as social sessions for patients, they offer fun, optional activities such as arts and

crafts while connecting with others going through similar experiences. “The attendees can

unburden and talk in a safe space,” says Amy. “It’s less about the activities and more about

opening up and gaining a sense of normalisation and validation. We oscillate between lots of

tears and lots of laughter.”

Outside of Hospice, it’s not uncommon for people to wonder about the emotional weight of

being a palliative care counsellor, and the resilience it must require. However, Maxine and

Amy agree that their careers are hugely fulfilling. “It’s so rewarding because we are

connecting with people at such a real, potent time in their lives,” says Maxine. “It’s such a

privilege. It’s an honour to be alongside and involved in people’s journey in that way,” adds

Amy. The pair agree that it is incredibly gratifying when they see a tangible difference in a

person as a counselling session progresses: they may feel calmer and more settled or have

a sense of relief or release.

Part of training to be a counsellor involves practicing professionalism and self-care. “Training

in relational counselling is all about the relationship – you’ve got to have the relationship

before anything else can happen. But we also learn to not ‘fall into’ the relationship – that’s

the professionalism, and that’s how you can do the work and not carry that out of the room,”

explains Maxine. “You learn how to hold a space that is about the person you are with,

without being triggered personally.”